Ragen Chastain is a lifelong athlete who holds the Guinness World Record for the heaviest female to complete a marathon race. The former competitive dancer set the record during a race in 2017 in Sanford, Maine, at age 40 and 288 pounds.

Like many athletes, Chastain, a Los Angeles-based certified health coach and author, has dealt with knee pain, but she says health care providers only see her weight when she seeks treatment.

Video of the Day

Video of the Day

"As a fat patient, I'm often told the only thing that could possibly help knee pain is weight loss, and that's simply not true," she says. "I'm an athlete who has been various weights, and when I had knee pain in a thinner body, I was given all kinds of options for what can be done."

Chastain is among the activists who say they and many others are discriminated against by the medical establishment and society at large because of their body size, based on the assumptions that they are inherently unhealthy, lack willpower and could easily become thin if only they made different choices.

They say this is despite the fact that research associating body size and negative health consequences is mixed, not to mention that the standard measures of body mass are flawed and long-term weight loss fails for most people.

Reclaiming 'Fat'

The weight bias Chastain and other activists describe touches every aspect of life for a wide swath of Americans. About three-quarters of all adults in the U.S. are considered to have a higher than "normal" weight, with approximately 40 percent who have obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As many as 4 in 10 people with obesity report facing size discrimination at work, school, home or a doctor's office, according to a March 2020 consensus statement in Nature Medicine from several major endocrinology, diabetes and obesity organizations.

One way advocates for the rights and wellness of larger people try to neutralize that stigma is to describe themselves and others using a term that has historically been a slur: fat.

"There's a fat acceptance movement," says Lindo Bacon, PhD, a Wayne, New Jersey-based nutritionist and physiologist and author of Health at Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight. "It's basically people saying, 'We're fat, we know it, but there's nothing wrong with it. We want to take the stigma away. We want to just own our bodies. It's OK to call us fat,' and so they're using the word without any of its pejorative connotations."

Yet being fat remains stigmatized, particularly in health care settings. "Medical discrimination is one of the primary concerns of people in fat activist communities and fat people in general," says Tigress Osborn, Phoenix-based chair of the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA), a fat rights organization. Those who opt not to lose weight or who try but have a hard time when counseled by doctors face the risk of being denied medical treatments or insurance coverage for some conditions, she says.

"You still deserve to be treated like a human being in the culture, even if you are not healthy."

Take Chastain's experience seeking treatment for knee pain. Knee joint replacement is a common surgical treatment, with more than 750,000 procedures performed in 2017, according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

Because having severe obesity raises the risk of serious complications before and after surgery, the AAOS says doctors may tell people to lose weight before surgery. Yet a February 2020 Journal of Arthroplasty study found 4 out of 5 patients who were denied knee or hip replacement because of severe obesity never reached the target weight for the procedure.

Meanwhile, a July 2017 study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery found people with severe obesity who did get knee replacements experienced comparable gains in functionality and pain relief as people with smaller bodies.

Related Reading

Why Fat Isn't Always Unhealthy

Partly to blame for anti-fat discrimination are the very standards used to define when people are above a "normal" size, Osborn says.

The first "ideal weight" tables were developed during the 1940s by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company as a way to predict how long life insurance policyholders might live, according to a May 2016 historical review article in the Journal of Obesity.

In 1985, the National Institutes of Health began using body mass index as a way to measure body fat. BMI is calculated by dividing a person's weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters. According to the CDC, those measurements are:

- Underweight: less than 18.5

- Healthy: 18.5 to 24.9

- Overweight: 25 to 29.9

- Class I Obesity: 30 to 34.9

- Class II Obesity: 35 to 39.9

- Class III Obesity: 40 and above

Anyone who falls into the overweight or obesity categories is presumed to have body fat that presents a risk to their health.

But critics of the BMI, such as Osborn, say that's too much of an assumption. She points to a February 2016 study in the International Journal of Obesity that concluded if people are deemed as healthy or unhealthy based on BMI alone, roughly 75 million adults in the U.S. are being misclassified.

That's because 48 percent of the people with overweight who were studied were actually healthy by measures like blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar. So were 29 percent of people with class I obesity and 16 percent of those with class II or III obesity. Meanwhile, 31 percent of people deemed to be at a healthy weight by BMI standards were categorized as unhealthy by other tests.

Plus, the link between increasing body fat and overall health is not a straight line. A frequently cited April 2005 Journal of the American Medical Association study found that having obesity or underweight (especially over age 70) was associated with excess deaths, while having overweight was actually associated with reduced mortality, compared with having a normal BMI.

The results held even after the study data were reanalyzed and published by the National Center for Health Statistics in June 2018, with adjustments made for smoking (which is associated with both lower body weight and excess deaths) and weight loss due to illness.

"There is no denial in the fat activist community that body weight and percentage of fat correlate with a lot of conditions. But we always remind people that correlation is not causation," Osborn says.

The Activists Advocating for a Weight-Neutral Approach

Also frustrating to people within the fat acceptance movement (and pretty much everyone else) is that the treatment prescribed for obesity rarely works in the long term, Osborn says. A frequently cited November 2001 analysis of weight-loss studies in the American Journal for Clinical Nutrition found people regained more than 80 percent of lost weight within 5 years.

"Humans are not good at weight loss," Osborn says. To put it another way, she says, what other type of treatment with such low odds of working would be so regularly prescribed?

Enter the Health at Every Size Movement (HAES), which promotes weight-neutral health care practices that "reject both the use of weight, size or BMI as proxies for health, and the myth that weight is a choice," according to the Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH). "[HAES] grew because some were feeling uncomfortable with the typical medical model which shames people about weight and tells people that thinner is better," Bacon says.

Chastain is a co-writer of the HAES Sheets, a series of "blame-free, shame-free" guides for common medical conditions. The guides examine conditions for which high BMI is a risk factor and list additional risk factors and diagnostic measures for people to ask their doctors about.

"When weight loss is recommended as the treatment, we can try to see, 'Well, what else is there that we should try and what does the research say? What are weight-neutral approaches to this?'" she says.

Bacon adds that HAES adherents also urge a greater focus on the social determinants of health that contribute to disease, such as discrimination, limited access to high-quality health care or a lack of funds to purchase nutritious food.

Tip

You can find a searchable online registry of health care and other service providers who have pledged to honor HAES values at HAESCommunity.com.

The Doctors Urging We Put Health First

The movement faces an uphill battle toward widespread acceptance, though. "I think the Health at Every Size Movement does not recognize the disease of obesity because often, if not exclusively, it has not taken the time to learn about the disease of obesity," says Fatima Cody Stanford, MD, MPH, an obesity medicine doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. "A lot of that comes from the fact that, unfortunately, most doctors aren't educated about this disease either."

She believes that identifying obesity as a disease actually removes blame from the individual, which is key in combatting weight bias, particularly in the medical community.

"Obesity is a disease that may or may not be influenced by behavior — same with diabetes, same with cancer — except the interesting thing is that we see all these diseases often caused by the obesity and it's the elephant in the room that we just don't treat," Dr. Stanford says. She adds that the most gratifying part of her job is deleting diagnoses from a patient's chart because the common denominator of obesity has been addressed.

She is in agreement with the HAES movement about one thing, though: "I do believe that I should respect patients, regardless of where their weight is. I'm not going to treat them negatively or stigmatize them."

The fact that certain lifestyle habits have health consequences can't be ignored, whether or not they are reflected in the amount of body fat a person has, says Sylvia Gonsahn-Bollie MD, an obesity medicine doctor in Richmond, Virginia and the author of Embrace You: Your Guide to Transforming Weight-Loss Misconceptions into Lifelong Wellness.

"I can have a patient who is 'normal' body weight but is not eating food that is helpful for their metabolic health, they're not exercising, their stress levels are high, they're not sleeping, they have a host of other factors that affect metabolic health," she says. "That is equally as lethal."

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie came to obesity medicine following her own journey gaining 60 pounds during pregnancy and then losing it; as such, she says her goal is not to have patients adhere to BMI standards, but rather to arrive at their own "happy weight" where their health is optimized and prioritized.

Ultimately, though, a history of no underlying medical conditions is not a requirement for being respected, Osborn says. "You still deserve to be treated like a human being in the culture, even if you are not healthy."

How to Unlearn Anti-Fat Bias

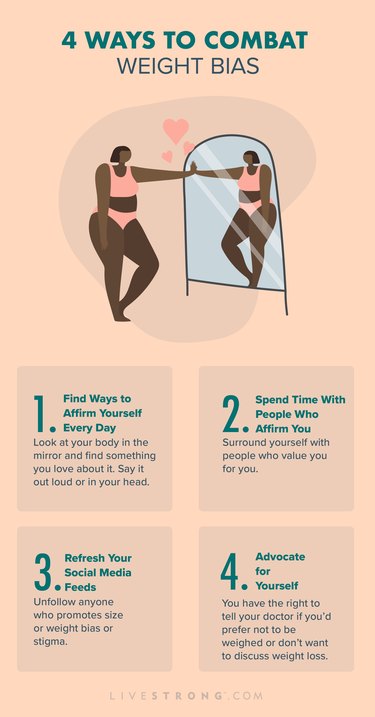

It shouldn't fall on individuals to eliminate weight discrimination in society — our health care system and policy-makers have work to do. But in the meantime, the following advice can help each of us deal with the internal biases we harbor and stand up for ourselves when others make weight an issue.

1. Find Ways to Affirm Yourself Every Day

"It's important to be able to see your body and find some way to love it," says Da'Shaun Harrison, managing editor of Wear Your Voice magazine, who writes about anti-fat bias.

"For me it has been being one of those people who stands in the mirror every single day and finds something about myself to affirm. I'm sort of forcing myself to define the beauty in my body."

2. Surround Yourself With People Who Affirm You, Too

"A lot of fat folks are stuck in friend groups with people who only see them as counselors, humorous people and not really people at all but as things who are only there to provide service for them," Harrison says. "I've surrounded myself with friends who affirm me as a beautiful, smart, funny, talented and gifted person."

3. Pay Attention to What You Read, Watch and Follow

After a lifetime of disordered eating, Brie Scrivner, PhD, a medical sociologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, says they decided to turn away from the anti-fat "aspirational" images they were seeing on traditional and social media.

"I decided I'm going to look for more people who look like me and who look different from me, and that was just the tip of the iceberg, because there are so many fat liberationists and HAES individuals putting out incredible content," Scrivner says. "I was hearing other people having the same experiences that I've had with health care, with bullying, with mental illness and I thought it was just me."

4. Acknowledge Your Insecurities

"We are taught from day one that insecurities are a bad thing, that they're something that we should not want to interrogate more deeply," Harrison says.

Instead, sit with your insecurities and allow them to guide you toward actions and situations that are more affirming. "Say, 'I'm going to lean into that, and now I can decide that because I feel this, I won't show up in this really unhealthy relationship or friendship that no longer does any good for me.'"

5. Know Your Rights

Weight discrimination is legal in many places throughout the U.S. NAAFA has a list of localities that afford some legal protections, as well as tools to advocate for expanding them.

6. Ask to Not Be Weighed

Many routine doctor's visits begin with a weigh-in. "If you're nervous about going to the doctor because being on the scale is triggering, you don't have to be weighed," says Beckie Hill, a vocational rehabilitation consultant in Seattle who follows HAES principles with clients. "You can decline to be weighed by the nurse. They may not understand it, but it is your right."

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie says about half of her patients opt not to be weighed or have their waist circumference measured even though they come to her to lose weight. Instead, they focus on lifestyle changes and overall wellness goals.

7. Tell Your Doctor You Won't Discuss Weight Loss

Just as you can decline to be weighed, you can explain to your doctor that weight loss is not a goal you're interested in pursuing.

Know that there's a financial incentive for your doctor to bring up losing weight, though, Hill says. Those discussions can be billed to your insurance company as weight-loss counseling, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Osborn says this happened to her during a follow-up visit after emergency-room treatment for COVID-19. "I went to look at my chart and it said that I had been given weight-loss counseling during my appointment. First of all, I hadn't. Second of all, it would be unconscionable to have a doctor dealing with a patient who just returned home from the hospital with COVID to advise them to lose weight in the middle of recovering."

8. Ask for the Same Level of Care as a Smaller Person

If a doctor tells you to lose weight to address a specific health condition, ask them: "What would you be telling me to do about this if I weren't fat?" Osborn says.

9. Insist on Equity

"Ask for the things you need," Osborn says. In a doctor's office, that might mean explaining that a blood pressure cuff or a gown is not big enough or that there aren't chairs that accommodate you or your loved ones in the waiting room. "It's OK to advocate for yourself and ask for those things."

- Guinness World Records: "Heaviest person to complete a marathon (female)"

- CDC: "Obesity and Overweight"

- World Health Organization: "Obesity"

- NPR: "American Medical Association House of Delegates Resolution 2013"

- Nature: "Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity"

- Obesity: "Internalizing Weight Stigma: Prevalence and Sociodemographic Considerations in US Adults"

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: "Total Knee Replacement"

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: "Obesity, Weight Loss, and Joint Replacement Surgery"

- Journal of Arthroplasty: "Fate of the Morbidly Obese Patient Who Is Denied Total Joint Arthroplasty"

- Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery: "Functional Gain and Pain Relief After Total Joint Replacement According to Obesity Status"

- Journal of Obesity: "For Researchers on Obesity: Historical Review of Extra Body Weight Definitions"

- CDC: "Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity"

- International Journal of Obesity: "Misclassification of cardiometabolic health when using body mass index categories in NHANES 2005–2012"

- JAMA: "Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity"

- National Center for Health Statistics: "Vital and Health Statistics"

- American Medical Association: "Report of the Council on Science and Public Health"

- American Journal for Clinical Nutrition: "Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies"

- The Association for Size Diversity and Health: "The Health at Every Size (HAES) Approach"

- Health at Every Size (HAES) Sheets

- NAAFA: Equality at Every Size